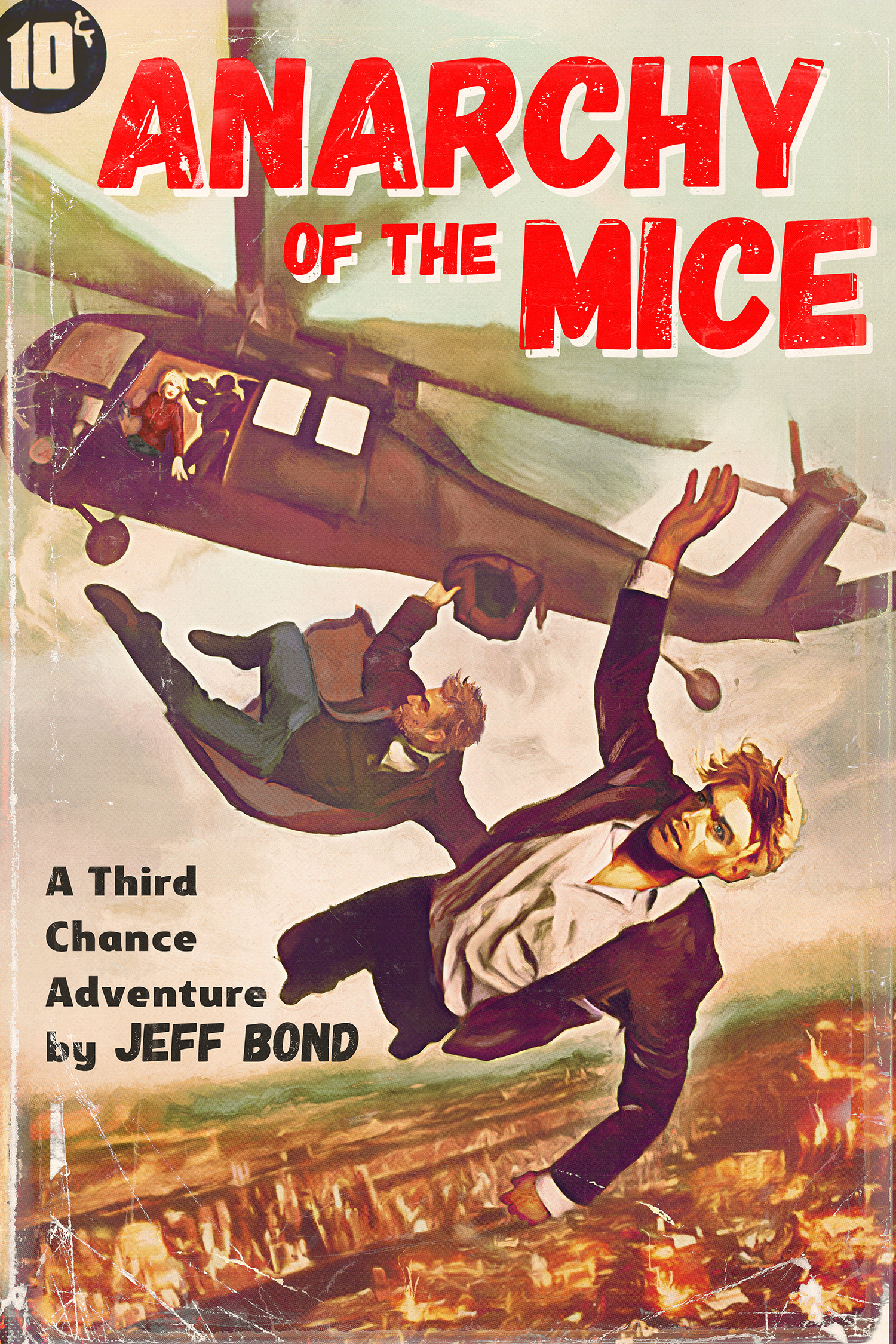

Anarchy of the Mice

Now available!

Scroll down for a sneak peek at the first four chapters!

From Jeff Bond, author of Blackquest 40 and The Pinebox Vendetta, comes Anarchy of the Mice, book one in an epic new series starring Quaid Rafferty, Durwood Oak Jones, and Molly McGill: the trio of freelance operatives known collectively as Third Chance Enterprises.

BlueInk Reviews (starred): “Bond’s three main characters leap off the page … hurtling from one life-threatening challenge to the next … a gripping thriller, sure to please its target audience and likely to have crossover appeal as well.”

Kirkus Reviews (starred): “Raucously entertaining … crackerjack action scenes … vividly evocative prose … The characters are colorful but rendered with complex nuance … Bond’s writing is well observed and engrossing in a range of registers.”

How far could society fall without data? Account balances, property lines, government ID records — if it all vanished, if everyone’s scorecard reset to zero, how might the world look? What savagery would take hold?

The Blind Mice are going to show us.

————

Molly McGill is fighting it. Her teenage son has come downstairs in a T-shirt from these “hacktivists” dominating the news. Her daughter’s bus is canceled — too many stoplights out — and school is in the opposite direction of the temp job she’s supposed to be starting this morning. She is twice-divorced; her P.I. business, McGill Investigators, is on the rocks; what kind of life is this for a woman a mere twelve credit-hours shy of her PhD?

Then the doorbell rings.

It’s Quaid Rafferty, the charming — but disgraced — former governor of Massachusetts, and his plainspoken partner, Durwood Oak Jones. The guys have an assignment for Molly. It sounds risky, but the pay sure beats switchboard work.

They need her to infiltrate the Blind Mice.

Danger, romance, intrigue, action for miles — whatever you read, Anarchy of the Mice is coming for you.

cover design and illustration by Ethan Scott

ANARCHY OF THE MICE

by Jeff Bond

PROLOGUE

Piper Jackson didn’t like the look that passed between her brother and the plant foreman, Mr. Sampson. She stood by them at a floor-to-ceiling window in the foreman’s office. Twelve stories down, a pair of police cruisers and a municipal van had entered the circle drive.

“Marcus.” Mr. Sampson backed away from the glass. “Can you get to the stuff?”

“Yeah, yeah, I’m on it.” Her brother pivoted for the door. “Dumpster?”

“Right.” Mr. Sampson ran to his computer, fingers jittery on the keys. “No! No, they’ll check the dumpster—use the cellar.”

Piper eyed the pair of men. Well, one man. Her brother was almost a man, nineteen.

She was seventeen. “What’re you typing? Why is he running off to the cellar?”

Mr. Sampson stayed focused on the screen. He pecked the keyboard standing up, tall like Marcus but stocky, handyman mustache.

Marcus said from the threshold, “You didn’t do a thing, Sis, remember,” then bolted.

Piper checked the window. Below, the cruisers had parked crookedly end-to-end. A woman burst from the van with a clipboard. She tossed hairnets to each of four officers and pulled one on herself, all of them hurrying for the entrance.

“I asked a question,” Piper said.

Mr. Sampson finished typing something. Whatever it was, it didn’t work. “Stupid thing won’t let me in. Can you get this file deleted while I go deal with this?”

“With what.”

“This! These…ah, inspectors. Dang it. I gotta go. Can you try to delete the file?”

Piper said she would. He stabbed out one last command, got honked at again, and rushed off.

She walked to the computer. The file Mr. Sampson had been clicking was named Q3productionCosts_true.

Why exactly would a person stick “_true” at the end of a filename?

Piper felt scared, mad, and vindicated—all at once. She’d known it. The second Marcus had gotten promoted out of the mail room to manufacturing trainee, four lousy months into the job. The leading producer of organic food in North America was going to trust her brother: a kid with no college and a rap sheet?

Mom had told her to quit being negative. “They’re investing in this city. They want to keep jobs in America. Why not Marcus?”

Then they’d made him full-time. Then two months later, he was deputy production manager. Manager? And that was supposed to be legit?

Now Piper tried opening Q3productionCosts_true and got the same error Mr. Sampson must have.

FILE IN USE BY ANOTHER USER.

She logged in with the credentials they’d granted her for the summer. Piper was unpaid. Mr. Sampson had needed somebody to de-crud his departmental computers but had no budget, so Marcus had suggested Piper. She had computer skills to burn but not the school kind, meaning this “internship” was about the best gig she could get.

A simple scan showed which other workstation was using the file. Piper remote-desktopped in and closed it. Then she switched back to Mr. Sampson’s machine and tried deleting it again.

As Q3productionCosts_true vanished from the screen, Piper felt a hiccup of doubt.

Was that smart?

Before she could worry much, her phone buzzed. A text from Marcus.

need 10 minutes, keep cops away from factory!

Piper sprinted for the stairs. Secretaries and salesmen leaned out of cubicles to see. Her elbow nicked a bowl of green apples, and two tumbled to the carpet.

She raced down eight flights before reaching a stairwell that overlooked the factory floor. Below, Marcus was struggling with a giant bag labeled Franklin Food Services, carrying it away from the grinder with backward-chopping steps.

The other factory worker, Russ Doan, watched him with hard eyes.

Piper kept bounding down, three stairs per stride, near free fall. She eased up into the last flight, hearing Mr. Sampson’s voice in the lobby.

“…heads-up would’ve been nice,” he was saying, “but of course we’ll cooperate. Can I take another look at that paperwork?”

The woman from the van handed over her clipboard peevishly. As Piper came to stand beside Mr. Sampson, the policemen raised their chins.

She raised hers back.

Mr. Sampson took a while reading. He moved the document closer and farther like it was written in a foreign language.

“As you know,” he began, “ingredients are our top priority at Harvest Earth. We could’ve outsourced to China like the competition and saved ourselves—”

“We need to see the factory,” the woman interrupted. “Now.”

“Right, yes…the factory. We can certainly show you the factory,” Mr. Sampson said, almost shouting in the direction of Marcus and Russ Doan.

How many of those Franklin Food bags had to get moved?

Piper said, “No. You can’t.”

The inspector looked at Piper. An aquiline nose and deep-sunk eyes pinched together menacingly. One cop smirked like he’d heard this hustle before.

Piper shuffled close to Mr. Sampson until there was no space separating them. With one hand, keeping that side of her body perfectly still, she unclipped the keyring from his belt. So the metal wouldn’t make noise disengaging, she pinned the keyring hard against the small of his back. Then she slid the keys behind her own back.

The keys were too big to hide in a fist so she dropped them into her pants. Over the underwear would’ve been better, but she misjudged fabrics and they ended up in her bare butt.

“Keys are up in the office,” she said. “I saw them hanging off the coat rack.”

Through their touching sides, Piper felt Mr. Sampson stop breathing.

“Shoot, that’s right,” he managed. “I forgot to bring them down. We’ll have to go upstairs.”

The woman grimaced, but when Mr. Sampson gestured to join him at the elevator banks, she did. The cops followed. Mr. Sampson flashed Piper a relieved look, then he snapped his fingers in the direction of the factory.

The second the outsiders had rounded the corner, Piper booked for the south entrance. Supply closets, printers, a water cooler—all whizzed by in her periphery. Approaching the door, she dug into her pants for the key ring, metal raking her crotch.

Marcus was carrying two Franklin Food bags backwards through the door.

“Dude,” Piper said. “What’s in there?”

“Cereal,” said Marcus’s voice from behind the bags.

“Cereal? Like Frosted Flakes?”

“No, like the cheapest crap there is by volume!” Marcus said, staggering to a nearby stairwell. “It’s filler, now help me get the rest downstairs.”

Piper puzzled a moment. “Where you even get that much cerea—”

“Who cares, grab a bag!” Marcus disappeared down the stairs.

Four more bags were stacked in an industrial locker. Piper looked to Russ Doan. Why isn’t he helping?

She hoisted a bag of cereal that must’ve weighed sixty pounds, squatting and wrapping her arms around the base. The top teetered and slammed into her face—she both heard and felt crunching through the burlap. She lurched to the door, knocking hard hats off hooks, crushing a sleeve of plastic packaging underfoot.

Marcus met her at the threshold. Without a word, he accepted the load and carried it the rest of the way to the cellar.

Piper caught her breath and hoisted another bag. She and her brother moved the next two without trouble.

Working together, her arms and thighs burning, Piper flashed back to the long days they used to put in helping Mom at the nursery—before the box stores drove it out of business. Toting around mulch, sprinkling handfuls in each other’s hair. Sweaty all summer. Before Marcus’s arrests.

Piper was struggling with the last bag when a hand gripped her sleeve.

“Time to face the music, you two.”

She turned to find Russ Doan with his lip pushed up, looking dumb and righteous.

Marcus was back from the cellar. “She’s got nothing to do with this.” He stepped up to Doan. “Take your hands off.”

Doan tightened his grip.

“Ow!” Piper said. “Why don’t you help? They find this stuff, it’s your job too.”

Russ Doan said nothing. She knew from Mr. Sampson, who dished gossip to her on slow days, that Doan had been with Harvest Earth eighteen years. The sole survivor from an original union workforce of three hundred. The production line, almost fully automated now, required only a certified machinist (Doan) and operator-manager (Marcus) to run.

That the operator-manager didn’t have to be union was a sore spot for Doan. Piper figured he had other beefs with Marcus.

Marcus took another step, bringing their faces an inch apart.

“I said hands off.”

Russ Doan sneered, all nose hair. “Figured it. Too good for honest work.”

There was a gloat at the corner of his mouth.

Piper said, “Shut the hell up,” and flinched away.

The bag broke. Cereal cascaded to the floor, covering all their shoes and Piper’s pants to the cuff in gray-yellow flakes. Dust filled her nose, dry corn-sweet stink. She retreated a step and trampled some, the sound like a million bugs festering.

Doan smiled.

From the side, Marcus decked him. Right fist to the ear. Doan fell in a heap, slumping into the cereal—more crackling bugs—then didn’t move.

“There’s cops here!” Piper said. “Stupid, man. You already got two strikes.”

They dragged Doan behind the thermoforming machine, making a trail of flakes. Marcus got brooms and they pushed the cereal out of sight. He got some down the drain and underneath the sink station. Piper made a pile in the recessed area behind a spinning whiteboard.

“There’s still a lot of dust,” she said. “You guys keep a Shop-Vac or something around?”

“In the supply closet.” Marcus wiped his brow and went for it.

Piper wondered how this would shake out, assuming they lucked out and got past today’s inspection. Would Doan keep quiet? Would Mr. Sampson have to pay him off or something? Maybe she and Marcus deserved hush money, too.

How much cash was this cereal-filler scam worth to Harvest Earth? The company had bilked the city for millions in tax breaks to keep the plant here. A city that was already bankrupt. Money that should’ve gone for roads and school lunches.

Returning to the grinder, Piper heard footsteps. She looked to the door expecting Marcus.

It was Mr. Sampson.

“Right this way, please,” he said, pulling his spare key from the lock. “Our wholesome-frank process is just over here.”

The inspector and her police escorts entered the factory floor warily. Marcus pulled up the rear—they must have bumped into him.

His face was ice.

The woman said, “Marcus here runs the whole show? Single operator?”

Mr. Sampson said they did have a second worker, but yes, the level of automation was impressive.

He looked from Piper to Marcus. “Where is, uh…Russ?”

All four cops swiveled to Marcus.

Piper said, “Russ stepped out. Had to pick up flowers for his wife.”

Mr. Sampson barely kept a straight face. Russ Doan didn’t say much, but when he did it was usually to complain about his wife. Sheila the Spender.

The inspector paced the floor, jotting notes on her clipboard. The cops poked after her like ducks.

“And every ingredient,” the woman said, “is organic. Non-GMO. Gluten-free. As declared in the certification?”

Mr. Sampson coughed. “Y—yes. Correct.”

The inspector capped her pen with clear disappointment. “Everything seems in order. We had an anonymous tip about some impure inputs. Must’ve been a prank.”

Piper and Marcus locked eyes, then looked without looking to the thermoformer.

Doan.

One cop said, “Smells over here.”

He was standing near the whiteboard.

Mr. Sampson volunteered, “Soy gets a little funky, very common.” He placed a hand on the inspector’s shoulder. “We should get y’on your way, that Friday traffic is murder—”

“Dust.” The inspector frowned. “There’s dust all over. Where did it come from?”

She shook off Mr. Sampson’s touch and started that way. The cop gripped the whiteboard between his thumb and forefinger and spun it parallel with the floor, revealing the mountain of cereal behind.

Piper felt her insides shrinking to a cold, brittle dot.

A different cop said, “What color is gluten?”

The inspector stabbed a cereal flake with her pen. As she raised it to eye-level, a lot was going on with Mr. Sampson. His hands were rubbing in front of his shirt. His mustache twitched, and the ingratiating smile below began to fade.

“Obviously there’s been a mistake,” he said.

“So it seems.” The inspector scooped a few flakes into a baggie, and on her command, two officers donned gloves and began gathering samples.

The remaining officers produced handcuffs from their belts.

Mr. Sampson said, “We—er, that is, I pride myself on giving my team free reign, but I never imagined…”

Again, all eyes found Marcus. Piper expected her brother to shout, or run, or grab the steel pitchfork leaning against the mixer.

Marcus didn’t do any of this. He just dropped his head.

The whole deal was rigged. Mr. Sampson had planned for this possibility, Piper saw now. He’d always given Marcus instructions privately, huddled in his office or some stairwell. He’d made Marcus the sole driver of the Harvest Earth van.

Marcus had been proud.

Piper didn’t need to check Mr. Sampson’s computer to know he wouldn’t have referenced the cereal-filler scheme in email—that the only electronic trace he’d left behind was that file.

The one Piper had just zapped.

“This is junk!” she said. “My brother didn’t do it, it wasn’t his idea.”

But Marcus was already cuffed. One of the baggie-filling cops had spotted Russ Doan, and Doan had revived enough to confirm everything Mr. Sampson was saying about Marcus: that he alone had managed the input stocks, that he sometimes acted shifty.

Piper ran at Mr. Sampson, driving her forehead into his side.

Marcus, wrists joined, managed to pull her off. “I’ll be okay.”

“No this is bullsh—”

“It’s how it is. How it is right now.”

The cops were jerking him away, tugging his collar, kicking the backs of his knees.

“But hey.” Marcus resisted to face Piper, to look at her square. “You get them back, Sis. You hear me? You get them back.”

Tears streamed down Piper’s face. “Get who back?”

Marcus’s expression darkened, a hint of that rage she had wanted him to show. His gaze traveled the factory walls and ceiling, seeming to penetrate studs and plaster and glass.

“Everybody,” he told her. “Get ’em all back. Every last cheat.”

PART ONE

SIX MONTHS LATER. NEW JERSEY

The first I ever heard of the Blind Mice was from my fourteen-year-old son Zach. I was scrambling to get him and his sister ready for school, stepping over dolls and skater magazines, thinking ahead to the temp job I was starting in about an hour, when Zach came slumping downstairs in a suspiciously plain T-shirt.

“Turn around,” I said. “Let’s see the back.”

He scowled but did comply. The clothing check was mandatory after that vomiting-skull sweatshirt he’d slipped out the door in last month.

Okay. No drugs, profanity, or bodily fluids being expelled.

But there was something. An abstract computer-ish symbol. A mouse? Possibly the nose, eyes, and whiskers of a mouse?

Printed underneath was, Nibble, nibble. Until the whole sick scam rots through.

I checked the clock: 7:38. Seven minutes before we absolutely had to be out the door, and I still hadn’t cleaned up the grape juice spill, dealt with my Frizz City hair, or checked the furnace. For twenty minutes I’d been hearing ker-klacks, which my heart said was construction outside but my head worried could be the failing heater.

How bad did I want to let Zach’s shirt slide?

Bad.

“Is that supposed to be a mouse?” I said. “Like an angry mouse?”

“The Blind Mice,” my son replied. “Maybe you’ve heard, they’re overthrowing the corporatocracy?”

His eyes bulged teen sarcasm underneath those bangs he refuses to get cut.

“Wait,” I said, “that group that’s attacking big companies’ websites and factories?”

“Government too.” He pulled his face back ominously. “Anyone who’s part of the scam.”

“And you’re wearing their shirt?”

He shrugged.

I would’ve dearly loved to engage Zach in a serious discussion of socioeconomic justice—I did my Master’s thesis on the psychology of labor devaluation in communities. Except we needed to go. In five minutes.

“What if Principal Broadhead sees that?” I said. “Go change.”

“No.”

“Zach McGill, that shirt promotes domestic terrorism. You’ll get kicked out of school.”

“Like half my friends wear it, Mom.” He thrust his hands into his pockets.

Ugh. I had stepped in parenting quicksand. I’d issued a rash order and Zach had refused, and now I could either make him change, starting a blow-out fight and virtually guaranteeing I’d be late my first day on the job at First Mutual, or back down and erode my authority.

“Wear a jacket,” I said—a poor attempt to limit the erosion, but the best I could do. “And don’t let your great-grandmother see that shirt.”

Speaking of, I could hear Granny’s slippers padding around upstairs. She was into her morning routine, and would shortly—at the denture rinsing phase—be shouting down that her sink was draining slow again; why hadn’t the damn plumber come yet?

Because I hadn’t paid one. McGill Investigators, the P.I. business of which I am the founder and sole employee (yes, I realize the plural name is misleading), had just gone belly-up. Hence the temp job.

Karen, my six-year-old, was seated cheerily beside her doll in front of orange juice and an Eggo waffle.

“Mommy!” she announced. “I get to ride to school with you today!”

The doll’s lips looked sticky—OJ?—and the cat was eyeing Karen’s waffle across the table.

“Honey, weren’t you going to ride the bus today?” I asked, shooing the cat, wiping the doll with a dishrag.

Karen shook her head. “Bus isn’t running. I get to ride in the Prius, in Mommy’s Prius!”

I felt simultaneous joy that Karen loved our new car—well, new to us: 120K miles as a rental, but it was a hybrid—and despair because I really couldn’t take her. School was in the complete opposite direction of New Jersey Transit. Even if I took the turnpike, which I loathe, I would miss my train.

Fighting to address Karen calmly in a time crunch, I said, “Are you sure the bus isn’t running?”

She nodded.

I asked how she knew.

“Bus Driver said, ‘If the stoplights are blinking again in the morning, I ain’t taking you.’” She walked to the window and pointed. “See?”

I joined her at the window, ignoring the driver’s grammatical example for the moment. Up and down my street, traffic lights flashed yellow.

“Blind Mice, playa!” Zach puffed his chest. “Nibble, nibble.”

The lights had gone out every morning this week at rush hour. On Monday the news had reported a bald eagle flew into a substation. On Tuesday they’d said the outages were lingering for unknown reasons. I hadn’t seen the news yesterday.

Did Zach know the Blind Mice were involved? Or was he just being obnoxious?

“Great,” I muttered. “Bus won’t run because stoplights are out, but I’m free to risk our lives driving to school.”

Karen gazed up at me, her eyes green like mine and trembling. A mirror of my stress.

Pull it together, Molly.

“Don’t worry,” I corrected myself. “I’ll take you. I will. Let me just figure a few things out.”

Trying not to visualize myself walking into First Mutual forty-five minutes late, I took a breath. I patted through my purse for keys, sifting through rumpled Kleenex and receipts and granola-bar halves. Granny had made her way downstairs and was reading aloud from a bill-collection notice. Zach was texting, undoubtedly to friends about his lame mom. I felt air on my toes and looked down: a hole in my hose.

Fantastic.

I’d picked out my cutest work sandals, but somehow I doubted the look would hold up with toes poking out like mini-wieners.

I wished I could shut my eyes, whisper some spell, and wake up in a different universe.

Then the doorbell rang.

CHAPTER TWO

Quaid Rafferty waited on the McGills’ front porch with a winning smile. It had been ten months since he’d seen Molly, and he was eager to reconnect.

Inside, there sounded a crash (pulled-over coat rack?), a smack (skateboard hitting wall?), and muffled cross-voices.

Quaid fixed the lay of his sportcoat lapels and kept waiting. His partner, Durwood Oak Jones, stood two paces back with his dog. Durwood wasn’t saying anything, but Quaid could feel the West Virginian’s disapproval—it pulsed from his bluejeans and cowboy hat.

Quaid twisted from the door. “School morning, right? I’m sure she’ll be out shortly.”

Durwood remained silent. He was on record saying they’d be better off with a more accomplished operative like Kitty Ravensdale or Sigrada the Serpent, but Quaid believed in Molly. He’d argued that McGill, a relative amateur, was just what they needed: a fresh-faced idealist.

Now he focused on the door—and was pleased to hear the deadbolt turn within. He was less pleased when he saw the face that appeared in the door glass.

The grandmother.

“Why, color me damned!” began the octogenarian, yanking the screen door. “The louse returns. Whorehouses all kick you out?”

Quaid strained to keep smiling. “How are you this fine morning, Eunice?”

Her face stormed over. “What’re you here for?”

“We’re hoping for a word with Molly if she’s around.” He opened his shoulders to give her a full view of his party, which included Durwood and Sue-Ann, his aged Bluetick Coonhound.

They made for an admittedly odd sight. Quaid and Durwood shared the same vital stats, six-one and a hundred-eighty-something pounds, but God himself couldn’t have poured two more different molds. Quaid in a sportcoat with suntanned wrists and mussed-just-so blond hair. Durwood removing his hat and casting steel-colored eyes humbly about, jeans pulled down over his boots’ piping. And Sue with her mottled coat, rasping like any breath could be her last.

Eunice stabbed a finger toward Durwood. “He can come in—him I respect. But you need to turn right around. My granddaughter wants nothing to do with cads like you.”

Behind her, a voice called, “Granny, I can handle this.”

Eunice ignored this. “You’re a no-good man. I know it, my granddaughter knows it.” Veins showed through the chicken-y skin of her neck. “Go on, hop a flight back to Vegas and all your whores!”

Before Quaid could counter these aspersions, Molly appeared.

His heart chirped in his chest. Molly was a little discombobulated, bending to put on a sandal, a kid’s jacket tucked under one elbow—but those dimples, that curvy body…even in the worst domestic throes, she could’ve charmed slime off a senator.

He said, “Can’t you beat a seventy-four-year-old woman to the door?”

Molly slipped on the second sandal. “Can we please just not? It’s been a crazy morning.”

“I know the type.” Quaid smacked his hands together. “So hey, we have a job for you.”

“You’re a little late—McGill Investigators went out of business. I have a real job starting in less than an hour.”

“What kind?”

“Reception,” she said. “Three months with First Mutual.”

“Temp work?” Quaid asked.

“I was supposed to start with the board of psychological examiners, but the position fell through.”

“How come?”

“Funding ran out. The governor disbanded the board.”

“So First Mutual…?”

Molly’s eyes, big and leprechaun green, fell. “It’s temp work, yeah.”

“You’re criminally overqualified for that, McGill,” Quaid said. “Hear us out. Please.”

She snapped her arms over her chest but didn’t stop Quaid as he breezed into the living room followed by Durwood and Sue-Ann, who wore no leash but kept a perfect twenty-inch heel by her master.

Two kids poked their heads around the kitchen door-frame. Quaid waggled his fingers playfully at the girl.

Molly said, “Zach, Karen—please wait upstairs. I’m speaking with these men.”

The boy argued he should be able to stay; upstairs sucked; wasn’t she the one who said they had to leave, like, immedia—

“This is not a negotiation,” Molly said in a new tone.

They went upstairs.

She sighed. “Now they’ll be late for school. I’m officially the worst mother ever.”

Quaid glanced around the living room. The floor was clutter-free, but toys jammed the shelves of the coffee table. Stray fibers stuck up from the carpet, which had faded beige from its original yellow or ivory.

“No, you’re an excellent mother,” Quaid said. “You do what you believe is best for your children, which is why you’re going to accept our proposition.”

The most effective means of winning a person over, Quaid had learned as governor of Massachusetts and in prior political capacities, is to identify their objective and articulate how your proposal brings it closer. Part two is always trickier.

He continued, “American Dynamics is the client, and they have deep pockets. If you help us pull this off, all your money troubles go poof.”

A glint pierced Molly’s skepticism. “Okay. I’m listening.”

“You’ve heard of the Blind Mice, these anarchist hackers?”

“I—well yes, a little. Zach has their T-shirt.”

Quaid, having met the boy on a few occasions, wasn’t shocked by the information. “Here’s the deal. We need someone to infiltrate them.”

Molly blinked twice.

Durwood spoke up, “You’d be great, Moll. You’re young. Personable. People trust you.”

Molly’s eyes were grapefruits. “What did you call them, anarchist hackers? How would I infiltrate them? I just started paying bills online.”

“No tech knowledge required,” Quaid said. “We have a plan.”

He gave her the nickel summary. The Blind Mice had singled out twelve corporate targets, “the Despicable Dozen,” and American Dynamics topped the list. In recent months AmDye had seen its websites crashed, its factories slowed by computer glitches, internal documents leaked, the CEO’s home egged repeatedly. Government agencies from the FBI to NYPD were pursuing the Mice, but the company was troubled by the lack of progress and so had hired Third Chance Enterprises to take them down.

“Now if I accept,” Molly said, narrowing her eyes, “does that mean I’m officially part of Third Chance Enterprises?”

Quaid exhaled at length. Durwood shook his head with an irked air—he hated the name, and considered Quaid’s branding efforts foolish.

“Oh, Durwood and I have been at this freelance operative thing awhile.” Quaid smoothed his sportcoat lapels. “Most cases we can handle between the two of us.”

“But not this one.”

“Right. Durwood’s a whiz with prosthetics, but even he can’t bring this”—Quaid indicated his own ruggedly handsome but undeniably middle-aged face—“back to twenty-five.”

Molly’s eyes turned inward. Quaid’s instincts told him she was thinking of her children.

She said, “Sounds dangerous.”

“Naw.” He spread his arms, wide and forthright. “You’re working with the best here: the top small-force, private-arms outfit in the Western world. Very minimal danger.”

Like the politician he’d once been, Quaid delivered this line of questionable veracity with full sincerity.

Then he turned to his partner. “Right, Wood? She won’t have a thing to worry about. We’d limit her involvement to safe situations.”

Durwood thinned his lips. “Do the best we could.”

This response, typical of the soldier he’d once been, was unhelpful.

Molly said, “Who takes care of my kids if something happens, if the Blind Mice sniff me out? Would I have to commit actual crimes?”

“Unlikely.”

“Unlikely? I’ll tell you what’s unlikely, getting hired someplace, anyplace, with a felony conviction on your application…”

As she thundered away, Quaid wondered if Durwood might not have been right in preferring a pro. The few times they’d used Molly McGill before had been secondary: posing as a gate agent during the foiled Delta hijacking, later as an archivist for the American embassy in Rome. They’d only pulled her into Rome because of her language skills—she spoke six fluently.

“…also, I have to say,” she continued, and from the edge in her voice, Quaid knew just where they were headed, “I find it curious that I don’t hear from you for ten months, and then you need my help, and all of a sudden, I matter. All of a sudden you’re on my doorstep.”

“I apologize,” Quaid said. “The Dubai job ran long, then that Guadeloupean resort got hit by a second hurricane. We got busy. I should’ve called.”

Molly’s face cooled a shade, and Quaid saw that he hadn’t lost her.

Yet.

Before either could say more, a heavy ker-klack sounded outside.

“What’s the racket?” Quaid asked. He peeked out the window at his and Durwood’s Vanagon, which looked no more beat-up than usual.

“It’s been going on all morning,” Molly said. “I figured it was construction.”

Quaid said, “Construction in this economy?”

He looked to Durwood.

“I’ll check ’er out.” The ex-soldier turned for the door. Sue-Ann, heaving herself laboriously off the carpet, scuffled after.

Alone now with Molly, Quaid walked several paces in. He doubled his sportcoat over his forearm and passed a hand through his hair, using a foyer mirror to confirm the curlicues that graced his temples on his best days.

This was where it had to happen. Quaid’s behavior toward Molly had been less than gallant, and that was an issue. Still, there were sound arguments at his disposal. He could play the money angle. He could talk about making the world safer for Molly’s children. He could point out that she was meant for greater things, appealing to her sense of adventure, framing the job as an escape from the hamster wheel and entrée to a bright world of heroes and villains.

He believed in the job. Now he just needed her to believe, too.

CHAPTER THREE

Durwood walked north. Sue-Ann gimped along after, favoring her bum hip. Paws echoed bootheels like sparrows answering blackbirds. They found their noise at the sixth house on the left.

A crew of three men were working outside a small home. Two story like Molly’s. The owner had tacked an addition onto one side, pre-fab sunroom. The men were working where the sunroom met the main structure. Dislodging nails, jackhammering between fiberglass and brick.

Tossing panels onto a stack.

“Pardon,” Durwood called. “Who you boys working for?”

One man pointed to his earmuffs. The others paid Durwood no mind whatsoever. Heavyset men. Big stomachs and muscles.

Durwood walked closer. “Those corner boards’re getting beat up. Y’all got a permit I could see?”

The three continued to ignore him.

The addition was poorly done to begin with, the cornice already sagging. Shoddy craftsmanship. That didn’t mean the owners deserved to have it stolen for scrap.

The jackhammer was plugged into an outside GFI. Durwood caught its cord with his bootheel.

“The hell?” said the operator as his juice cut.

Durwood said, “You’re thieves. You’re stealing fiberglass.”

The men denied nothing.

One said, “Call the cops. See if they come.”

Sue-Ann bared her gums.

Durwood said, “I don’t believe we need to involve law enforcement,” and turned back south for the Vanagon.

Crime like this—callous, brash—was a sign of the times. People were sore about this “new economy,” how well the rich were making out. Groups like the Blind Mice thought it gave them a right to practice lawlessness.

Lawlessness, Durwood knew, was like plague. Left unchecked, it spread. Even now, besides this sunroom dismantling, Durwood saw a half-dozen offenses in plain sight. Low-stakes gambling on a porch. Coaxials looped across half the neighborhood roofs: cable splicing. A Rottweiler roaming off leash.

Each stuck in Durwood’s craw.

He walked a half-block to the Vanagon. He hunted around inside, boots clattering the bare-metal floor. Pushed aside Stinger missiles in titanium casings. Squinted past crates of frag grenades in the bulkhead he’d jiggered himself from ponderosa pine.

Here she was—a pressurized tin of Black Ops epoxy. Set quick enough to repel a flash airstrike, strong enough to hold a bridge. Durwood had purchased it for the Dubai job. According to his supplier, Yakov, the stuff smelled like cinnamon when it dried. Something to do with chemistry.

Durwood removed the tin from its box and brushed off the pink Styrofoam packing Yakov favored. Then allowed Sue a moment easing herself down to the curb before starting back north.

Passing Molly’s house, Durwood glimpsed her through the living room window. She was listening to Quaid, fingers pressed to forehead.

Quaid was lying. Which was nothing new, Quaid stretching the truth to a woman. But these lies involved Molly’s safety. Fact was, they knew very little of the Blind Mice. Their capabilities, their willingness to harm innocents. The leader, Josiah, was a reckless troublemaker. He spewed his nonsense on Twitter, announcing targets ahead of time, talking about his own penis.

The heavyset men were back at it. One on the roof. The other two around back of the sunroom, digging up the slab.

Durwood set down the epoxy. The men glanced over but kept jackhammering. They would not be the first, nor last, to underestimate this son of an Appalachian coal miner.

The air compressor was set up in the lawn. Durwood found the main pressure valve and cranked its throat full-open.

The man on the roof had his ratchet come roaring out of his hands. He slid down the grade, nose rubbing vinyl shingles, and landed in petunias.

Back on his feet, the man swore.

“Mind your language,” Durwood said. “There’s families in the neighborhood.”

The other two hustled over, shovels at their shoulders. The widest of the three circled to Durwood’s backside.

Sue-Ann coiled her old bones to strike. Ugliness roiled Durwood’s gut.

Big Man punched first. Durwood caught his fist, torqued his arm round behind his back. The next man swung his shovel. Durwood charged underneath and speared his chest. The man wheezed sharply, his lung likely punctured.

The third man got hold of Durwood’s bootheel, smashed his elbow into the hollow of Durwood’s knee. Durwood scissored the opposite leg across the man’s throat. He gritted his teeth and clenched. He felt the man’s Adam’s apple wriggling between his legs. A black core in Durwood yearned to squeeze.

He resisted.

The hostiles came again, and Durwood whipped them again. Automatically, in a series of beats as natural to him as chirping to a katydid. The men’s faces changed from angry, to scared, to incredulous. Finally they stayed down.

“Now y’all are helping fix that sunroom.” Durwood nodded to the epoxy tin. “Mix six-to-one, then paste ’er on quick.”

Luckily he’d caught the thieves early, and the repair was uncomplicated. Clamp, glue, drill. The epoxy should increase the R-value on the sunroom ten, fifteen units. Good for a few bucks off the gas bill in winter, anyhow.

Durwood did much of the work himself. He enjoyed the panels’ weight, the strength of a well-formed joint. His muscles felt free and easy as if he were home, ridding the sorghum fields of johnsongrass.

Done, he let the thieves go.

He turned back south toward Molly’s house. Sue-Ann scrabbled alongside.

“Well, ol’ girl?” he said. “Let’s see how Quaid made out.”

CHAPTER FOUR

I stood on my front porch, watching the Vanagon rumble down Sycamore. My toes tingled, my heart was tossing itself against the walls of my chest, and I was pretty sure my nose had gone berserk. How else could I be smelling cinnamon?

Quaid Rafferty’s last words played over and over in my head: “We need you.”

For twenty minutes, after Durwood had taken his dog to investigate ker-klacks, Quaid had given me the hard sell. The money would be big-time. I had the perfect skills for the assignment: guts, grace under fire, that youthful je ne sais quoi. Wasn’t I always saying I ought to be putting my psychology skills to better use? Well, here it was: understanding these young people’s outrage would be a major component of the job.

Some people will anticipate your words and mumble along. Quaid did something similar but with feelings, cringing at my credit issues, brightening with whole-face joy at Karen’s reading progress—which I was afraid would suffer if I got busy and didn’t keep up her nightly practice.

He was pitching me, yes. But he genuinely cared what was happening in my life.

I didn’t know how to think about Quaid, how to even fix him in my brain. He and Durwood were so far outside any normal frame of reference. Were they even real? Did I imagine them?

Their biographies were epic. Quaid the twice-elected (once impeached) governor of Massachusetts, who now battled villains across the globe and lived at Caesars Palace. Durwood a legend of the Marine Corps, discharged after defying his commanding officer and wiping out an entire Qaeda cell to avenge the death of his wife.

I’d met them during my own unreal adventure—the end of my second marriage, which unraveled in tragedy in the backwoods of West Virginia.

They’d recruited me for three missions since. Each was like a huge, brilliant dream—the kind that’s so vital and packed with life that you hang on after you wake up, clutching backwards into sleep to stay inside.

Granny said, “That man’s trouble. If you have any sense in that stubborn head of yours, you’ll steer clear.”

I stepped back into the living room, the Vanagon long gone, and allowed my eyes to close. Granny didn’t know the half of it. She had huffed off to watch her judge shows on TV before the guys had even mentioned the Blind Mice.

No, she meant a more conventional trouble.

“I’ve learned,” I said. “If I take this job, it won’t be for romance. I’d be doing it for me. For the family.”

As if cued by the word “family,” a peal of laughter sounded upstairs.

Children!

My eyes zoomed to the clock. It was eight twenty. Zach would be lucky to make first hour, let alone homeroom. In a single swipe, I scooped up the Prius keys and both jackets. My purse whorled off my shoulder like some Super-Mom prop.

“Leaving now!” I called up the stairwell. “Here we go, kids—laces tied, backpacks zipped.”

Zach trudged down, leaning his weight into the rail. Karen followed with sunny-careful steps. I sped through the last items on my list—tossed a towel over the grape juice, sloshed water onto the roast, considered my appearance in the microwave door and just frowned, beyond caring.

Halfway across the porch, Granny’s fingers closed around my wrist.

“Promise me,” she said, “that you will not associate with Quaid Rafferty. Promise me you won’t have one single thing to do with that lowlife.”

I looked past her to the kitchen, where the cat was kinking herself to retch Eggo waffle onto the linoleum.

“I’m sorry, Granny.” I patted her hand, freeing myself. “It’s something I have to do.”