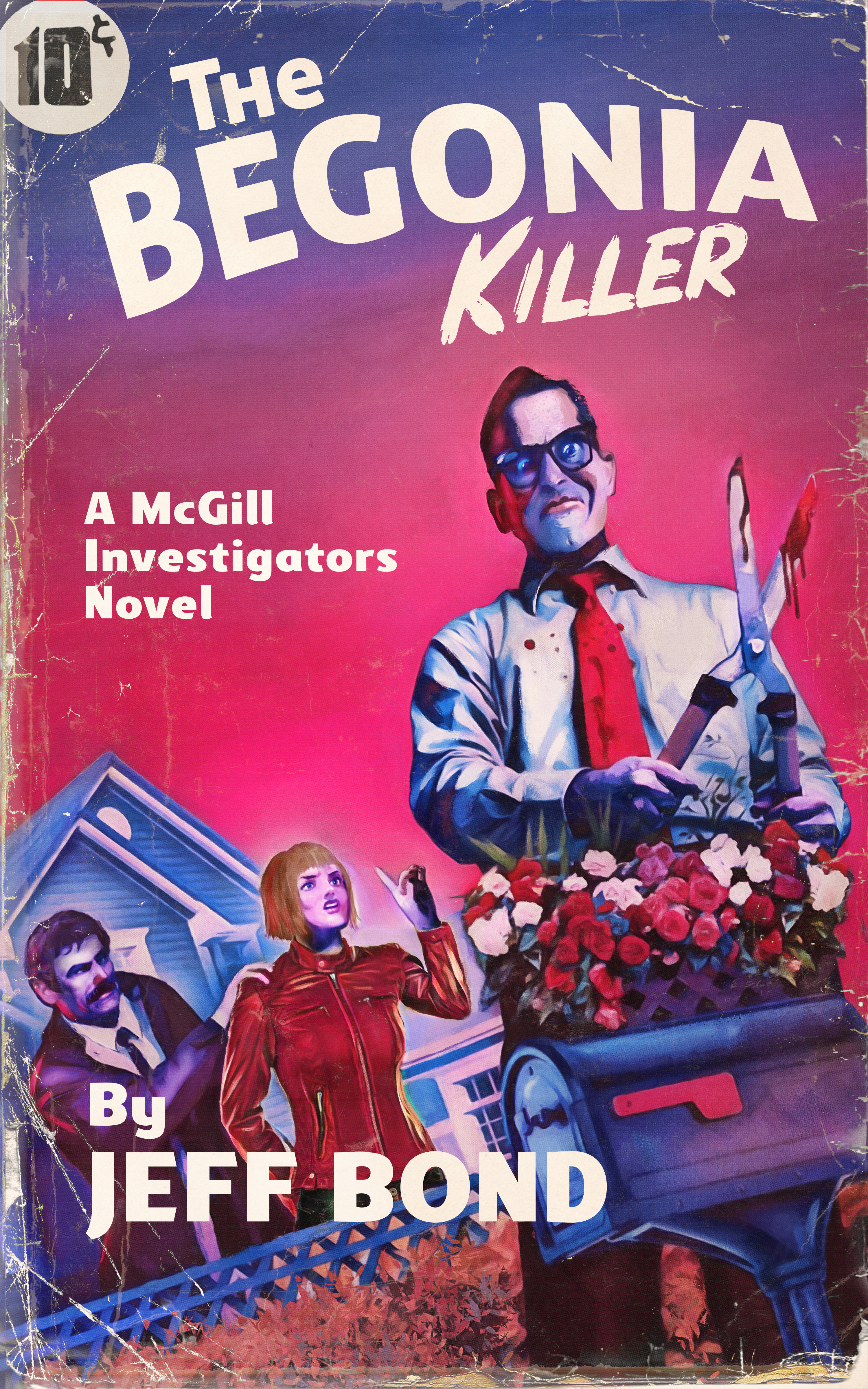

The Begonia Killer (McGill Investigators)

Now available for pre-order, releasing June 1, 2021.

Scroll down for a sneak peek at the first three chapters.

You know Molly McGill from her death-defying escapes in Anarchy of the Mice, book one of the Third Chance Enterprises series. Now ride along for her first standalone caper, The Begonia Killer.

When Martha Dodson hires McGill Investigators to look into an odd neighbor, Molly feels optimistic about the case — right up until Martha reveals her theory that Kent Kirkland, the neighbor, is holding two boys hostage in his papered-over upstairs bedroom.

Martha’s husband thinks she needs a hobby. Detective Art Judd, who Molly visits on her client’s behalf, sees no evidence worthy of devoting police resources.

But Molly feels a kinship with the Yancy Park housewife and bone-deep concern for the missing boys.

She forges ahead with the investigation, navigating her own headstrong kids, an unlikely romance with Detective Judd, and a suspect in Kent Kirkland every bit as terrifying as the supervillains she’s battled before alongside Quaid Rafferty and Durwood Oak Jones.

The Begonia Killer is not your grandparents’ cozy mystery.

THE BEGONIA KILLER

By Jeff Bond

Chapter One

After twenty minutes on Martha Dodson’s couch, listening to her suspicions about the neighbor, I respected the woman. She was no idle snoop. She’d noticed his compulsive begonia care out the window while making lavender sachets from burlap scraps. She hadn’t even been aware of the papered-over bedroom above his garage until her postal carrier had commented.

I asked, “And the day he removed the begonias, how did you happen to see that?”

Martha set tea before me on a coaster, twisting the cup so its handle faced me. “Ziggy and I were out for a walk—he’d just done his business. I stood up to knot the bag…”

Her kindly face curdled, and I thought she might be remembering the product of Ziggy’s “business” until she finished, “Then we saw him start hacking, and scowling, and thrusting those clippers at his flowers.”

Her eyes, a pleasing hazel shade, darkened at the memory.

She added, “At his own flowers.”

I shifted my skirt, giving her a moment. “The begonias were in a mailbox planter?”

“Right by the street, yes. The whole incident happened just a few feet from passing cars, from the sidewalk where parents push babies in strollers.”

“Did he dispose of the mess afterward?”

“Immediately,” Martha said. “He looked at his clippers for a second—the blades were streaked with green from all those leaves and stems he’d destroyed—then he sort of recovered. He picked everything up and placed it in the yard-waste bin. Every last petal.”

“He sounds meticulous.”

“Extremely.”

I jotted Cleaned up begonia mess in my notebook.

Maybe because of my psychology background—I’m twelve credit-hours shy of a PhD—I like to start these introductory interviews by allowing clients time to just talk, open-ended. I want to know what they feel is important. Often this tells as much about them as it does about whatever they’re asking me to investigate.

Martha Dodson had talked about children first. Hers were in college. Did I have little ones? I’d waived my usual practice of withholding personal information and said yes, six and fourteen. She’d clapped and rubbed her hands. Wonderful! Where did they go to school?

Next we’d talked crafting. Martha liked to knit and make felt flowers for centerpieces, for vase arrangements, even to decorate shoes—that type of crafter whose creativity spills beyond the available mediums and fills a house, infusing every shelf and surface.

Only with this groundwork lain had she told me about the case itself, describing the various oddities of her neighbor three doors down, Kent Kirkland.

I was still waiting to hear the crux of her problem, the reason she wanted to hire McGill Investigators. (Full disclosure—although the name is plural, there’s only one investigator: Molly McGill. Me.)

“That sounds like an intense, visceral moment,” I said, squaring myself to Martha on the couch. “So has he done something to your flowers? Are you engaged in a dispute with him?”

Martha shook her head. Then, with perfect composure, she said, “I think he’s keeping a boy in the bedroom over his garage.”

I felt like somebody had blasted jets of freezing air into both my ears. The pen I’d been taking notes with tumbled from my hand to the carpet.

“Wait, keeping a boy?” I said.

“Yes.”

“Against his will? As in, kidnapping?”

Martha nodded.

I was having trouble reconciling this woman in front of me—cardigan sweater, hair in a layered crop—with the accusation she’d just uttered. We were sitting in a nice New Jersey neighborhood. Nicer than mine. We were drinking tea.

She said, “There might be two.”

Now my notebook dropped to the carpet.

“Two?” I said. “You think this man is holding two boys hostage?”

“I don’t know for sure,” she said. “If I knew for sure, I’d be over there breaking down the door myself. But I suspect it.”

She explained that a ten-year-old boy from the next town over had gone missing six months ago. The parents had been quoted as saying they “lost track of” their son. They hadn’t reported his disappearance until the evening after they’d last seen him.

“The mother told reporters he wanted a scooter for Christmas, one of those cute kick scooters.” Martha sniffled at the memory. “Guess what I saw the UPS driver drop off on Kent Kirkland’s porch two weeks ago?”

“A scooter,” I said.

Her eyes flashed. “A very large box from a company that makes scooters.”

Having retrieved my notebook, I jotted, box delivery (scooter?). We talked a bit about this scooter company—which also made bikes, dehumidifiers, and air fryers.

Scooter or not, there remained about a million dots to be connected from this boy’s case, which I vaguely remembered from news reports, to Kent Kirkland.

I left the dots aside for now. “How do you get to two boys?”

“There was another missing boy, about the same age. During the summer.” Martha’s mouth moved in place like she was counting up how many jars of tomatoes she’d canned yesterday. “He lived close, too. That case was complicated because the parents had just divorced, and the dad—who was a native Venezuelan—had just moved back. People suspected him of taking the boy with him.”

“To Venezuela?”

“Yes. Apparently the State Department couldn’t get any answers.”

I nodded, not because I accepted all that she was telling me, but because there was no other polite response available.

Neither of us spoke. Our eyes drifted together down the street to Kent Kirkland’s two-story saltbox home. Pale yellow vinyl siding. Tall privacy fence. Three separate posted notices to “Please pick up after your pet.” Neighborhood Watch sign at the corner.

Finally, I said, “Look, Mrs. Dodson. Martha. Most of the cases we handle at McGill Investigators are domestic in nature. Straying husbands. Teenagers mixed up with the wrong crowd. I’m a mother myself, and I’ve been a wife. Twice.” I softened this disclosure with a smirk. “I generally take cases where my own life experiences can be brought to bear.”

“But that’s why I chose you.” Martha worried her hands in her lap. “Your website says, ‘Every case will be treated with dignity and discretion.’ That’s all I ask.”

I looked into her eyes and said, “Okay.”

She seemed to sense my reluctance and started, rushing, “Those bedroom windows are papered-over twenty-four hours a day! And the begonias, you didn’t see him destroy those begonias! I saw how he severed their stalks and shredded their root systems. You don’t do that to flowers you’ve tended for an entire season. Not if you’re a person of sound mind.”

“Gardening is more challenging for some than others. I love rhododendrons, but I can’t keep them alive. I over-water, I under-water. I plant them in the wrong spot.”

“Have you ever massacred them in a fit of rage?”

“No.” I smiled. “But I’ve wanted to.”

Martha couldn’t help returning the smile. But her eyes stayed on Kent Kirkland’s house.

I said, “Some men aren’t blessed with impulse control. Maybe he was a lousy gardener, he’d tried fertilizing and everything else, and the plants just refused to—”

“But he wasn’t a lousy gardener. He was excellent. I think he grew those begonias from seed. He wanted them to be perennials, is my theory, but we’re in zone seven—they’re annuals here. He couldn’t accept them dying off.”

Again, I was at a loss. I liked Martha Dodson. She had seemed like a reasonable person, right up until she’d started talking about kidnappings and Venezuela.

She scooted closer on the couch. “You didn’t see the rage, Miss McGill. I saw it. I saw him that day. He walked out of the garage with hand pruners, but he took one look at those begonias—leaves browning at the edges, stems tangled like green worms—and flipped out. He turned right around, put away the hand pruners and came back with clippers.”

She mimed viciously snapping a pair of clippers closed.

“Rage is one thing,” I said. “Kidnapping is another.”

“Of course,” Martha said. “That’s why I’d like to hire you: to figure out what he might be capable of.”

Her pupils seemed to pulse in place.

“I want to help you out, honestly.” I took her hand. “I do.”

“Is it money? I—I could pay you more. A little.”

Saying this, she seemed to linger on my jacket. I’d recently swapped out my boiled wool standby for this slightly flashier one, red leather with zippers. I had no great ambitions about an image upgrade; it’d just felt like time for a change.

“The fee we discussed will be sufficient,” I said. Martha had mentioned she was paying out of her own pocket, not from her and her husband’s joint account. “My concern is more about the substance of the case. It feels a bit outside my expertise.”

She clasped her hands at her waist. “Is it a question of danger? Do you not handle dangerous jobs?”

I balked. In fact, I’d done extremely dangerous jobs before, but only as part of Third Chance Enterprises, the freelance small-force, private arms team led by Quaid Rafferty and Durwood Oak Jones. We’d stopped an art heist in Italy. We’d saved the world from anarchist-hackers. Sometimes I can hardly believe our missions happened. They feel like half dream, half blockbuster movies starring me. Every couple years, just about the time I start thinking they really might be dreams, Quaid shows up again on my front porch.

“I don’t mind facing danger on a client’s behalf,” I said. “But McGill Investigators isn’t meant to replace the proper authorities. If you believe Mr. Kirkland is involved in these disappearances, your first stop should be the police.”

“Mm.” Martha’s face wilted, reminding me of those unlucky begonias. “Actually, it was.”

“You spoke with the police?”

She nodded. “Yes. Well, more of a front desk person. I told him exactly what I’ve been telling you today.”

“How did he respond?”

There was a floor loom beside the couch. Martha threaded her fingers through its empty spindles, seeming to need its feel.

“He said the department would ‘give the tip its due attention.’ Then on my way out, he asked if I’d ever read anything by J.D. Robb.”

“The mystery writer?” I asked.

“Right. He told me J.D. Robb was really Nora Roberts, the romance novelist. He said I should try them. He had a hunch I’d like them.”

My teeth were grinding.

I said, “Some men are idiots.”

Martha’s face eased gratefully. “Oh, my husband thinks the same. I’m a Yancy Park housewife with too much time on her hands. He says Kirkland’s just an odd duck. When I told him about the begonias, he got this confused expression and said, ‘What’s a perennial?’”

I could relate. My first husband had once handed me baking soda when I asked for cornstarch to thicken up an Italian beef sauce. The dish came out tasting like soap. After I traced back the mistake, he grumbled, “Ah, relax. They’re both white powders.”

As much as I probably should have, I couldn’t refuse Martha. Not after this conversation.

“I suppose I can do some poking around,” I said. “See if he, I don’t know, buys suspicious items at the grocery store. Or puts something in his garbage that might have come from a child.”

Martha lurched forward and clutched my hands like I’d just solved the case of Jack the Ripper.

“That would be amazing!” she cried. “Thank you so much! I know this seems far-fetched, but my instincts tell me something’s wrong at that house. If I didn’t follow through, if it turned out I was right and those little boys…”

She didn’t finish. I was glad.

CHAPTER TWO

The state of New Jersey offers private investigator licenses, but I’ve never gotten one. It doesn’t entitle you to much, and you have to put up two hundred and fifty dollars, plus a three-thousand-dollar “surety bond.” Besides the money, you’re supposed to have served five years as an investigator or police officer. Which I haven’t.

For all these reasons, my first stop after taking any case involving possible crimes is the local police station. Sometimes the police are impressed enough by what I tell them to assign their own personnel, usually some rookie detective or beat cop.

Other times, not.

“Begonias, huh?” said Detective Art Judd, lacing his fingers behind a head of bushy brown hair. “The ones with the thick, fluffy flower heads?”

“You’re thinking of chrysanthemums,” I said.

“Nnnno, I feel like it was begonias.”

“Not begonias. Maybe peonies?”

“Don’t think so,” he said. “I’m pretty sure the gal in the garden center said begonias.”

I was annoyed—one, at his stubborn ignorance of flowers, and two, that he’d segued so breezily off the subject of Kent Kirkland.

“The only other possibility with a thick, fluffy flower-head would be roses,” I said. “But if you don’t know what a rose looks like, you’re in trouble.”

Art Judd’s lips curled up below a mustache. “You could be right.”

I waited for him to return to Kirkland, to stand and pace about his sparsely decorated office, to offer some comment on the bizarre behavior I’d been describing for the last twenty minutes.

But he just looked at me.

Oh, I didn’t mind terribly being looked at. He was handsome enough in a best-bowler-on-his-Tuesday-night-league-team way. Broad sloping shoulders, large hand gestures that made the physical distance between our chairs feel shorter than it was.

I’d come for Martha Dodson, though.

“Leaving aside what is or isn’t a begonia,” I said, “how would you feel about checking into Kent Kirkland? Maybe sending an officer over to his house.”

He finally gave up his stare, kicking back from his metal desk with a sigh. “The department barely has enough black-and-whites to service the parking meters downtown.”

“I’m talking about missing boys. Not parking meters.”

“Point taken,” he said. “Why didn’t Mrs. Dodson come herself with this information?”

“She did. Your front desk person brushed her off.”

The detective looked past me into the precinct lobby. “They see a lot of nut jobs. You can’t go calling in the calvary every time someone comes in saying their neighbor hung the wrong curtains.”

“They aren’t curtains,” I said. “The windows are papered-over. Completely opaque.”

He rubbed his jaw. I thought he might be struggling to keep a straight face.

I continued with conviction I wasn’t sure I actually felt, “I saw it. It isn’t normal how he obscures that window. Martha thinks it’s weird, and it is weird.”

“Weird,” he said flatly. “Two votes for weird.”

“You put those Neighborhood Watch signs up, right?” In response to his slouch, I stood. “You encourage citizens to report anything out of the ordinary. When a citizen does so, the proper response would seem to be gratitude—or, at the very least, respect.”

This, either the words or my standing up, finally pierced the detective’s blithe manner.

“Okay, I give. You win.” His barrel chest rose and fell in a concessionary breath. “It’s true, with police work you never know which detail matters until it matters. Please apologize to Mrs. Dodson on behalf of the department. And I’ll be sure to have a word with Jimmie.”

He gestured to the lobby. “Kid’s been getting too big for his britches for a while now.”

I thanked him, and he ducked his head in return.

Then he said, “I suppose she thinks one of those boys being held is Calvin Witt.”

The boy whose parents had lost track of him.

“Yes,” I said. “The timing does fit.”

I considered mentioning the scooter, Calvin’s Christmas wish, but decided not to. We didn’t need to go down the rabbit hole of box shapes and labeling, and whether grown men rode scooters.

Detective Judd looked ponderously at the ceiling. I didn’t expect him to divulge information about a live case, but I thought if he knew something exculpatory—that Calvin Witt had been spotted in Florida, say—he might pass it along and save me some trouble.

“I hate to say this, but I honestly doubt young Calvin is among the living.” Art Judd smeared a hand through his mustache. “The father gambled online. Mom wanted out of the marriage, bad. She told anybody in her old sorority who’d pick up her call. Both of them methheads.”

“That’s disheartening,” I said. “So you think the parents…”

He nodded, reluctance heavy on his brow. “It’ll be a park, under some tree. Downstream on the banks of the Millstone. Pray to God I’m wrong.”

I matched his glum expression, both a genuine reaction and a professional tactic to encourage more disclosure. “Does the department have staff psychologists, people who study these dysfunctional family dynamics? Who’re qualified to unpack the facts?”

“Eh.” Art Judd flung out his arm. “You do this job long enough, you start recognizing patterns.”

This was a common reaction to the field of psychology: that it was just everyday observation masquerading as science, than anyone with a little horse sense could practice it.

I said, “Antipathy between spouses doesn’t predict antipathy toward the offspring, generally.”

The detective’s face glazed over like I’d just recited Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

“Perhaps I could conduct an interview,” I said. “As a private citizen, just to hear more background on Calvin?”

He chuckled out of his stupor. “Good try. You’re free to call as you like, but I don’t think the Witts are real receptive to interview requests now—with the exception of the paying sort.”

I crossed my legs, causing my skirt to shift higher up my knee. “Is there any further background you’d be able to share? You personally?”

His gaze did tick down, and he seemed to lose his first word under his tongue.

“Urb, I—I guess it’s all more or less leaked in the press anyway,” he said, and proceeded to give me the story—as the police understood it—of Calvin Witt.

Calvin had a lot to overcome. His parents, besides their drug and money problems, were morbidly obese, and had passed this along to Calvin. A social worker’s report found inadequate supplies of fresh fruit and lean proteins at the home. They’d basically raised him on McDonald’s and ice cream sandwiches. Calvin had learning and attention disorders. He started fights in school. His parents couldn’t account for huge swaths of his day, of his week even.

“They let him run like the junkyard dog,” Detective Judd said. “All we know about the night he disappeared, we got off the kid’s bus pass. Thankfully it’d been registered. We know he boarded a bus downtown, late.”

I opened my mouth to ask a follow-up.

“Before you get ideas,” he said, “no, the route didn’t pass anywhere near Martha Dodson’s neighborhood. We always crosscheck Yancy Park in these cases. That’s where the Ferguson place is.”

“Ferguson?”

“Yeah. Big rickety house, half falling over? Looks like the city dump. You shoulda passed it on the way.”

I shook my head.

“Well,” he continued, “that’s where the Fergusons live, crusty old married couple. Them and whatever riffraff needs a room. Plenty of crime there. Squalor. The neighbors keep trying to get it condemned.”

I definitely didn’t remember driving past a place like that. “Were there any witnesses who saw Calvin on the bus? Saw who he was with?”

“Nobody who’d talk.”

“Camera footage?”

The detective palmed his meaty elbow. “Have you seen the city’s transportation budget?”

I incorporated the new information, thinking about Kent Kirkland. He was single according to Martha. Mid-thirties. He worked from home—something to do with programming or web design, she thought.

Did he have a car? I’d noticed a two-car garage, but I hadn’t seen inside.

Did he go out socially? To bars? Or trivia nights?

Could he have ridden the bus downtown?

“Martha mentioned another case,” I said. “Last summer, I think it was. Another boy in the same vicinity?”

At first, Detective Judd only squinted.

I prompted, “There was some connection to Venezuela. The father was born there, maybe he—”

“Right, that Ramos kid!” Judd smacked his forehead. “How could I forget? Talk about red tape, my gosh. So he’s boy number two, is that it?”

I couldn’t very well answer “yes” to a question posed like that.

I simply repeated, “Martha mentioned the case.”

“Yep. That was a doozy.” As he remembered, he walked to a file cabinet and pulled open a drawer. “Real exercise in frustration.”

“There was trouble with the Venezuelan government?”

“And how.” He swelled his eyes, thumbing through manila folders, finally lifting out an overstuffed one. “I must’ve filled out fifty forms myself, no joke.”

He tossed the file on his desk. Documents slumped from the folder out across his computer keyboard.

I asked, “You never located the boy?”

“Not definitively. We had a witness put him with the paternal grandparents, the day before Dad put the whole crew on a plane.”

“Did you interview him?”

“Who?”

“The father.”

Detective Judd burbled his lips. “Nope. The Venezuelans stonewalled us—never could get him, not even on the horn. He told some website he had no clue where the kid was, but come on. They took him.”

I’d been following along with his account, understanding the logic and sequence—until this. I thought about Zach, my fourteen-year-old, and what lengths I would’ve gone to if he’d disappeared with his father.

“So you…stopped?” I said.

He stiffened. “We hit a brick wall, like I said.”

“Yes, but a boy had been taken from his mother. What did she say? Was she satisfied with the investigation?”

“No.” Judd’s mouth tightened under his mustache. His tone turned challenging. “Nobody’s satisfied when they don’t like the outcome.”

I tugged my skirt lower, covering my knee.

He continued, “I get fifty-some cases across my desk every week, Miss McGill. I don’t have the luxury of devoting my whole day to chasing crackpot theories just because somebody looks angry snipping their flowers.”

“Of course,” I said. “Which makes me the crackpot.”

He closed his eyes, as though summoning patience. “You seem like a nice lady. And look, I admit I’m a Neanderthal when it comes to matters—”

“‘Nice lady’ puts you dangerously close to pre-Neanderthal territory.”

He smiled. In the pause, two buttons began blinking on his phone.

“Pleasant as it’s been getting acquainted with you,” he said, “I can’t commit resources to this begonia guy. Just can’t. If you can pursue it without stepping over any legal boundaries, more power to you.”

I felt heat rising up my neck. I gathered my purse.

“I will pursue it. Two little boys’ welfare is on the line. Somebody needs to.”

He spread his arms wide, good-naturedly, stretching the collar of his shirt. “Hey, who better than you?”

The contents of the folder labeled Ramos were still strewn over his keyboard. “I don’t suppose I could borrow this file…”

“Official police documents?”

“Just for twenty minutes. Ten—I could flip through in the lobby, jot a few notes.”

He’d walked around his desk to show me out, and now he stopped, hands on hips, peering down at the file. The top paper had letterhead from the Venezuelan consulate.

I stepped closer to look with him, shoulder-to-shoulder. Our shoes bumped.

“Or even just this letter,” I said. “So I have the case number and contact information for the consulate. Surely there’s no harm in that?”

Detective Judd didn’t move his shoe. He smelled like bagels and coffee.

He placed his fingertip on the letter and pushed it my way.

“I can live with that.”

“Thanks,” I said, grinning, snatching the paper before he could reconsider.

CHAPTER THREE

I drove home through Yancy Park, thinking to get a second look at Kent Kirkland’s property. As I pulled into the subdivision, I noticed a dilapidated house up the hill, off to the west. It rose three stories and had bare-wood sides. Ragged blankets flapped over its attic windows.

The Ferguson place.

Somehow I’d missed it driving in from the other direction. Art Judd had been right: the place was an eyesore. Gutters dangled off the roof like spaghetti off a toddler’s abandoned plate. A refrigerator and TV were strewn about the dirt yard, both spilling their electronic guts.

I made a mental note to ask Martha Dodson about the property. I found it curious she suspected Kirkland instead of whoever lived in this rats’ den. Art Judd had mentioned crosschecking Yancy Park. Maybe the police had already been out and investigated to Martha’s satisfaction.

I kept driving to Martha and Kent Kirkland’s street. I slowed at the latter’s yard, peering over a rectangular yew hedge to a house that was the polar opposite of the Ferguson place. The paint job was immaculate. Gutters were not only fully affixed, but contained not a single leaf or twig. Trash bins were pulled around the side into a nook, out of sight.

Now that I knew the missing boys’ backstories, my brain was bursting with scenarios. How would the logistics work if Kirkland did have them?

How would he run errands? Did that bedroom door lock from inside? Were the windows reinforced so the boys couldn’t bust them out, or soundproofed so they couldn’t scream to passersby? How about doctor visits? What happened if they got sick? They must be missing their vaccinations.

I drove on, fully aware that Martha’s theory remained a longshot. Any number of factors might explain Kent Kirkland’s behavior. Obsessive parents. A brush with instability early in life. Maybe his father had mislaid some check that nearly put the family out on the street, so that now Kent couldn’t stomach a single scrap of paper, morsel of food, or flower petal out of place.

Everybody’s situation can look bizarre from a distance.

Exhibit 1-A: my own porch half an hour later as I pulled up the driveway. Its front railing—which lay somewhere in between Ferguson and Kirkland on the Needs Paint scale—was lined with stuffed animals. Twenty or twenty-five, ordered smallest to tallest.

I parked my beloved Prius, which I’d bought used as a high-mileage rental, and walked up the porch steps.

My six-year-old, Karen, was just backing through the screen door carrying more stuffies in her arms—and between her fingers, and pinned to her sides, and balanced in the crook of her neck…

“Do you need some help?” I asked.

“No,” she said. Then Blue Elephant slipped from her grasp, followed by Hedgie Hedgehog. “Actually, uh, maybe?”

I leaned down and got Blue Elephant and Hedgie in a single scoop, then walked them to the railing. “It looks like you have a preferred order.”

“I do,” she said, her chin high and smiling—that smile I would’ve moved mountains for.

We slotted the newcomers in their proper places. Hedgie’s height was exactly the same as Paddington’s, but Hedgie got the taller, leftward spot because “Paddington has a hat and that’s no fair.”

I helped Karen ferry another load of stuffies out to the porch. “Why are we doing this, Honey?”

“Because Simba peed again,” she said, speaking of our litter box-challenged cat. “They all have to get smell-tested.”

Ah, yes. That makes sense.

Well, six-year-old sense.

“And you felt like the smell-tests needed to be done outside?”

“Obviously.” She rolled her eyes—green, perfect mirrors of my own. “You have to do smell-tests in nature, it’s fresher.”

I had to concede that nature was, no doubt, fresher than my house.

I pointed to her hair, gathered in a pair of uneven clumps. “Want me to redo your ponytails?”

She shook her head vigorously. “Sophie Simpson does her own hair every morning, by herself. I’m starting too.”

With delicate touches, she gauged the shape of her hairdo. The left ponytail started near her temple while the right was high, almost a straight-up whale spout look.

“You know how we brush out your hair every night?” I said. “We do that because—”

“I know, I know about brushing out!” She tried pulling some of her right bangs across her forehead to the left ponytail. “This is how I want it.”

The tangled mess was turning my stomach a little. That one hairband would need to be cut out with scissors, I thought.

There’s a fine line between allowing kids to learn from mistakes, and standing pat as they dig themselves deeper and deeper into the abyss.

“Alright,” I said. “I’ll let you problem solve. I need to go inside and check on Zach.” I gestured to the stuffies. “Can I come back later and help you smell-test?”

“Once I have them all ready. It has to be equal for testing.”

“Right,” I said. “Equal.”

I left her to continue tweaking the stuffies’ order. Inside, there was no sign yet of Granny, who was supposed to be watching the kids. Presumably Zach was around—I’d seen his skateboard leaning against the house.

Now I stood in the middle of the living room surrounded by loose art supplies, library books, mail, a basket of unfolded laundry.

What would Art Judd think of all this?

I scolded myself for the thought. Art Judd wasn’t interested in me. I just happened to be in his office, a woman in a skirt, so he’d responded. I could’ve been a female lawyer, a cop, a secretary bringing him copies.

More importantly, I wasn’t interested in him. There was too much happening in my life. I was scraping to keep the lights on and mortgage paid. Zach’s algebra grade was the pits. Karen had a wonderful disposition and imagination, but her interest in reading hadn’t sparked like I’d hoped.

My head felt wet. Why did my head feel wet?

I twisted my neck around to check, then got a drop straight in my eye.

The ceiling was dripping.

“Zach!” I shouted, bolting for the stairs.

I took them three at a time, lunging, panting. I dashed through the hall to the bathroom. In my peripheral vision, I caught a glimpse of Zach in his room—checking himself out in a mirror.

I reached the bathroom.

“Zach, oh…Zach,” I said with a falling heart.

The sink had run over, a small but relentless stream of water flowing from the basin, across the counter, onto the tile below. An array of hair products—gels, sprays, molding muds—was spread across the vanity.

My first step inside sloshed. I banged closed the hot water tap, then hustled to the linen closet for towels—kicking off my sopping shoes.

There were no towels.

I dashed to the hamper. I grabbed the first four dirty towels I saw. Two of my sweaters and a mess of kid socks tagged along in the folds.

“A little help would be nice!” I said, back in the bathroom, tossing everything in my hands onto the minor lake.

I spread the towels on all fours until the area was covered. Then I tamped them down using my hands, elbows, kneecaps, blotting up water, desperate to keep as much as I could from draining through the floor and first-floor ceiling. I hoped this new jacket was waterproof.

I’d just taken my first breath, the mess contained, when Zach appeared in the doorway.

“Whoa,” he said. “Mucho wet.”

“Yeah, mucho,” I agreed, gathering up the towels that—on the bright side—could go right back into the hamper. “Care to tell me what happened?”

He shifted between feet, eyes searching, a confused series of calculations seeming to occur behind them. His bangs were glossy and wavy and stiff all at once.

“I just moistened my hair.” He touched it gingerly. “I know I turned the water off.”

With my chin, I indicated the sopping mass of terrycloth. “You definitely did not.”

“I did!” He threw up his arms in protest. “Karen must’ve come in here and turned it on when I was in my room.”

“She’s downstairs arranging her stuffies on the porch.”

“Maybe she took a break. Have you been observing her, like, constantly? Do you know for a fact she wasn’t up here messing with the water?”

I closed my eyes. I tried ignoring the angry thrum in my brain and the towels’ moisture, which had now penetrated to my bra.

Calmly, I said, “Why couldn’t you just use the mirror in the bathroom?”

“Seriously, Mom? This mirror sucks.”

“Please stop using that word,” I said. “And this is a vanity.” I pointed to the ten light-bulbs above the mirror. “It’s the clearest mirror in the house.”

He sneered at his reflection. “It makes my bangs look…off. Unnatural.”

He teased them away from his forehead. Half the hairs stayed just where he released them. The other half fell.

If I’d been arguing on the merits, I would’ve informed him that how his bangs looked in this mirror was how his bangs looked, period.

But I wasn’t arguing on the merits. I was arguing with a teenager.

“It’s just the angle.” I reached up and fixed the fallen hairs. “There. Now they look, you know, normal. Like normal bangs. All set.”

He cut his eyes warily at the mirror, but I could see the corners of his mouth relax.

Kids and hair. Ugh.

Now Zach did help me clean up. We finished in the bathroom, then headed downstairs to the living room, where Zach stood on tiptoes pressing paper towels into the ceiling’s bloated, blistering paint. We extracted all the moisture we could. The ceiling still had a damp spot sagging a half-inch below the rest.

Now it needed paint too.

I asked, “What happened to Granny?”

My seventy-four-year-old grandmother, Eunice, lived with us. When I’d left this afternoon to meet Art Judd, she had assured me she would keep an eye on the place.

Zach said, “She fell asleep.”

Shuffling sounded from the stairs, followed by a shrill voice.

“Nobody fell asleep!” Granny said. “I shut my eyes, is all. At no point were either of those two young persons left unsupervised.”

In her slippers and lavender robe, Granny tottered sourly into the living room. She saw the ceiling.

“Goodness.” She blinked. “Molly, you’d better do something about that.”

“Yes, Granny.” I worked up a smile. “I suppose I’d better.”

With a skeletal hand, she gripped my elbow in approval before heading off to watch TV—either cable news or a judge show.

From the porch came a familiar series of bloops and blip-de-whoops.

“Karen…” I called, starting that way.

Outside, my daughter was hunched in a corner, using her body as a shield as she played on my phone.

“Please hand it over,” I said.

“What? I was just trying this game,” she said.

“You’ve ‘tried’ SparklePopper about a hundred times,” I said. “You know you’re not allowed on my phone.”

“But Sophie Simpson plays her mom’s phone all the time.”

“That’s between Sophie and her mother.”

“She even texts her mom’s boyfriends. She gets to pick out what emojis they use.”

“Wonderful.” I held out my palm, waiting. “Those must be precious moments when they’re deciding between winky face and heart-eyes smiley face.”

Karen giggled, but I felt instantly bad about the snark.

I continued, “You know my feelings about electronics. Other families may do it differently, but we are going to interact with each other. I’m raising humans, not button-pushers.”

She surrendered the phone.

I participated in smell-testing all her stuffies. Zach and even Granny got into the act, crinkling their faces at those needing enzyme treatment, flashing thumbs up at the rest.

Finally, in the few minutes remaining before I needed to start dinner, I flattened the letter from the Venezuelan consulate in front of me on the kitchen table.

It said nothing substantial, basically that the consulate had received the request to compel Esteban X. Ramos to speak with the Hicks County Police Department, and would render a determination as to the request’s validity within ninety days.

The letterhead listed two phone numbers, one with a country code and another a toll-free 800 number.

I tried the 800 number first and got an earful of high-pitched screech. Their fax number?

I cringed tapping out the second number, imagining what Verizon was going to charge me for all these digits. A woman picked up on the fourth ring.

“Hola, puedo ayudarte?”

“Uh, yes,” I said. “I’m calling from the United States, trying to get some information about a missing persons case.”

A scrape sounded over the line, then the woman’s voice got louder like she’d picked up the speaker phone.

“Excuse me, what is your request?” the woman said. “Do you have a name with which you wish to speak?”

I got zip. I tried pressuring the woman to transfer me to someone important, an ambassador or high-placed functionary, but she kept suggesting I “contact my liaison in the United States, who has access to this information.”

Having worked switchboard temp jobs for Rainey Personnel during McGill Investigators’ many lean periods, I understood the woman’s situation. She had no power. She was told little and allowed to reveal even less, dooming her to be shouted at all day.

I thanked her and hung up.

The microwave clock read 4:48. I needed to start dinner. Earlier in the day, I’d been thinking beef stroganoff. Now I was thinking deli turkey sandwiches.

What am I supposed to do about Kent Kirkland?

The boys’ side of the case looked impassable. Venezuela wouldn’t talk to me. Calvin Witt’s parents were under intense media scrutiny—they weren’t going to talk to me.

I thought about calling Durwood Oak Jones, my Third Chance partner. Durwood was surprisingly good with computers and, less surprisingly, excellent at making people answer questions.

I thought about calling Martha Dodson and saying that on second thought, the case just wasn’t for me. I’d tried Detective Judd. I’d called the Venezuelan consulate. If she wanted me to stakeout Kirkland or rifle through his bin on trash-pickup day, I would, but I had to be honest. I doubted much would come of it.

Then I thought about Martha taking the news. Those hazel eyes fixing me hopefully, hands busy with some craft. How deflated she would be.

How when her husband got home and asked how her day had gone, she would smile and say, “Just fine,” and not mention her brief foray into hiring a private investigator.

I thought about those boys.

And I decided there was only one thing to do.

“Granny?” I said, grabbing my keys and purse. “You know where I keep the deli turkey, right?”

I was going to Kent Kirkland’s house. I was getting inside.